BLOG / BLOG POST

The Importance of Diversity in the Food Justice Movement

By Grace Edelen

Grace Edelen was a recent 2021 summer fellow at Green 2.0 and a graduate of Bellarmine University where she earned a Bachelor of Science in Environmental Science with a minor in Anthropology. She completed her undergraduate research on the effects of climate change on medicinal plants, analyzing how this shift affects Indigenous communities in Ecuador. Grace is passionate about supporting Green 2.0’s mission of making environmental causes more inclusive and equitable.

The more I learn about urban planning, the more I’m aware of food deserts – regions that lack fresh fruits and vegetables for at least 10 miles. Instead of local or sourced produce and meat, highly processed foods are found in public spaces such as gas stations, fast food restaurants, and corner stores. For residents experiencing multi-dimensional poverty, cheap food is a necessity. However, with very few nutritional options, food deserts hasten and exacerbate malnutrition, obesity, and ultimately decrease educational and economic achievement.

Food deserts were created by urban sprawl, with white residents moving toward the outer edges of cities, taking with them funding for shopping centers and the privilege of healthy food options. The overarching trend of urban sprawl and development has racist, ableist, and classist origins. For example, grocery chains invest in regions that are known to have high property values because this means more profit for those larger chains. This also means residents who are not wealthy cannot afford nutritional, healthy food.

Thankfully, the food justice movement actively works to combat the spread of food deserts. Beginning in 1996, the food justice movement developed out of the Community Food Security Coalition, which sought to provide affordable, healthy food to all Americans. While the motive was rooted in compassion and inclusion, there was a lack of diversity as most organizers were white. Additionally, stakeholder involvement was at a low with many of the food insecure residents ignored. The topic of race was completely left out of the conversation.

While I like to believe that this has improved, I still see topics like urban farming or food justice shrouded in whiteness. What is often forgotten is that urban farming and food production has deeply indigenous roots. People of color have been at the center of raising our food and creating the diets we all eat, yet they don’t receive the credit.

Let’s take a moment to acknowledge and admire some urban farms and fresh markets that are owned by people of color and are making an impact:

“True food justice work employs people who are impacted by food apartheid and live where the work is done,” Fresh Future Farm, Charleston, South Carolina.

“After realizing my family lives in a food desert…I quickly realized the need to teach others how to use their inner-city spaces to grow their own foods and find ways to feed their family fresh,” said Whitney Powers, founder of Garden Girl Foods, Louisville, Kentucky.

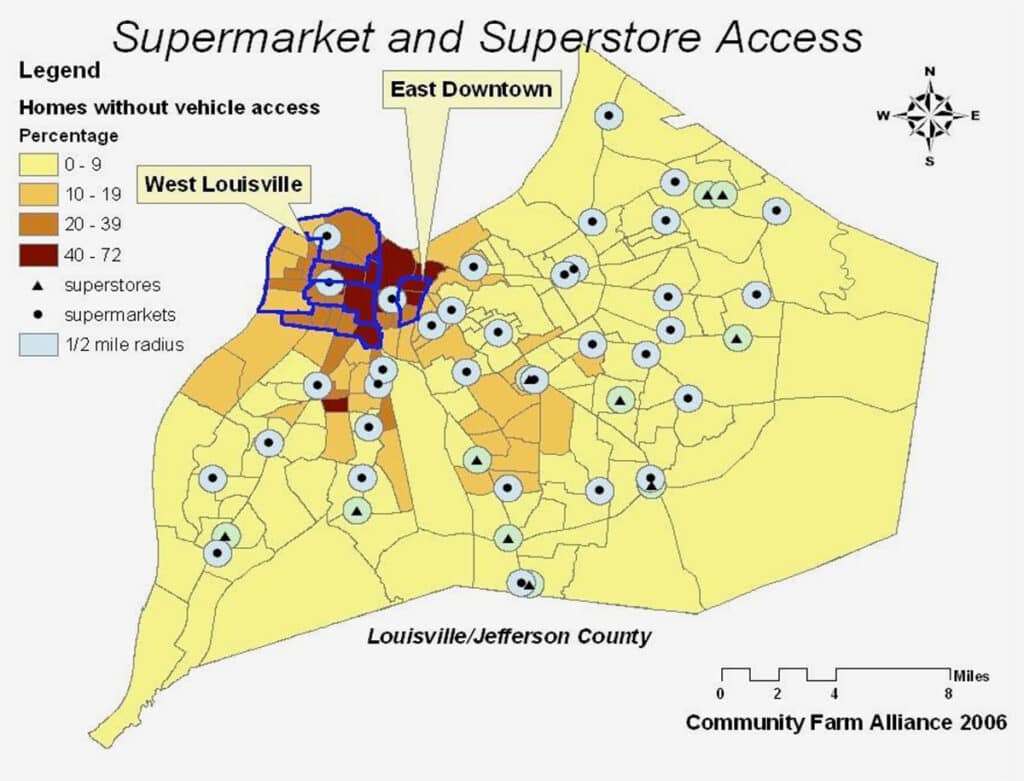

Right: Image of food deserts in Louisville, Kentucky from 2010 Report “The State of Food” produced by the University of Louisville.

Diversity must be at the center of any conversation around food justice. Urban farms have been a direct product of the movement, but white saviorism and privilege run rampant through the organizations, lessening the impact and contributing to the gentrification of many neighborhoods. It is important that while we work to combat the existing injustices, we also elevate the work of people of color farmers and activists who have been at the forefront of this movement for decades.

One big question that deserves an answer: why do white people feel the need to build additional urban farms instead of supporting and funding existing ones operated by people of color? Amplifying diversity in this movement creates a culture where individuals living in a food desert can trust the healthy food being grown in their neighborhoods and may become part of the solution. This means white people should step back and make room for diversity in the movement.

I understand the hypocrisy in the idea that I, as a white woman, am writing this piece. I ask myself: am I part of the problem? To some extent, I think yes. At the same time, I want to be part of the solution by stepping back and checking how much space I occupy. In this way, I can teach myself to listen and learn instead of jumping in to “help,” when maybe my help is not needed.

For more information about Grace Edelen, follow Grace on Twitter @maad_gracie.

Green 2.0 is accepting applications for its Winter 2022 cohort. Learn more: https://diversegreen.org/careers/.